Prairie Season at Whitnall Park

An Article Written by Mariette Nowak, former director of Wehr Nature Center, for the Greendale Village Life, August 20, 1975.

This article from Wehr’s archives describes the origin of Wehr’s prairie and highlights tallgrass prairie natural history. The prairie was called “Whitnall Park prairie” in 1975 since it was established ten years before Wehr Nature Center was built. Notice the reference to changing state statutes to allow for establishing native prairie plantings. We owe the current popularity of native gardens to these pioneers who experimented with prairie propagation and advocated for the protection and restoration of our native prairies.

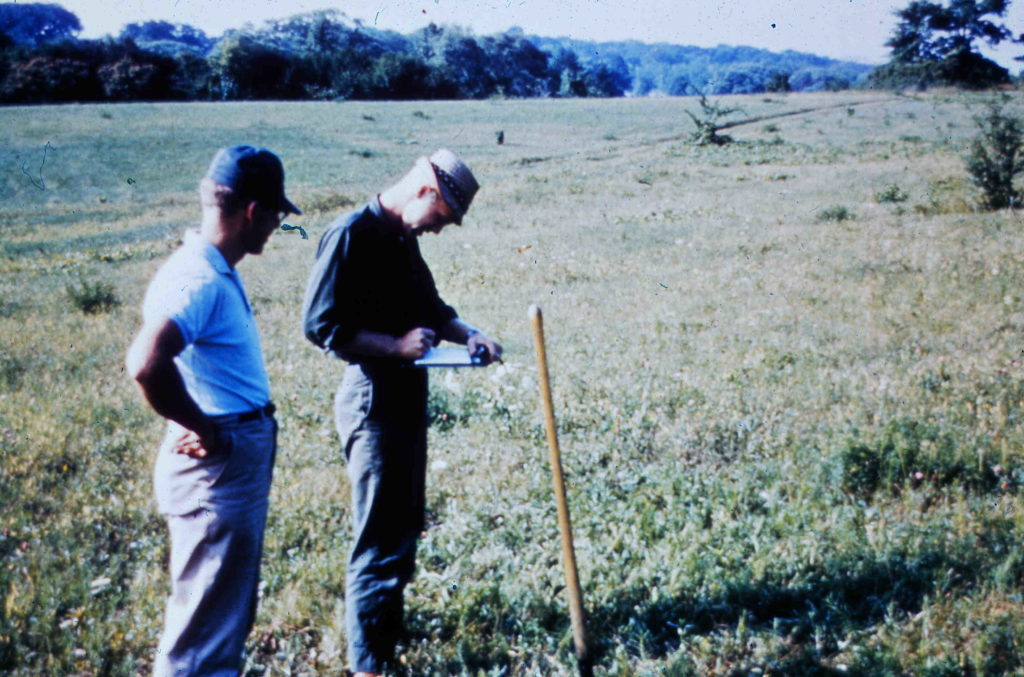

This is the season when the prairie at Whitnall Park in Hales Corners is at its peak. A waving sea of purples, golds, and whites against a green grassy backdrop greeted hikers recently. Philip Whitford, a botanist from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee led an interpretative visit to the prairie site sponsored by the Wehr Nature Center.

Former chairman of the UWM botany department, Dr. Whitford has been researching prairies for over 20 years. The prairie restoration at Whitnall Park, said Whitford, was begun ten years ago in 1965 by Arthur Ode, then assistant director of the Boerner botanical gardens and now assistant superintendent of Milwaukee County parks. Prairie grass seeds were purchased commercially, while most of the flower seeds were collected by hand.

Prairie plants are extremely slow growing and take a long to develop the deep roots which allow them to withstand the dry desiccating conditions of a midsummer prairie. Even a year after the initial planting at Whitnall Park, few native prairie plans could be seen. Gradually, over the years more and more prairie plants emerged as they managed to compete successfully with the weeds (those plants which first come into a disturbed area and are replaced by other species).

Periodic burning, says Whitford, is required to maintain the Whitnall Park prairie. Usually, this is done in mid-April after the weeds have sprouted but before native prairie plants have broken the ground. In this way, a fire can rid the area of weeds, invading shrub and tree species, as well as dead surface materials-all of which pave the way for prairie vegetation.

Native Americans originated the practice of burning the prairies. Their purpose was to stem the invasion of woodland into prairie areas which served as a habitat for the buffalo which provided them with almost all their necessities. “The cow and plow have done away with most of the original prairie,” said Whitford. Today in Wisconsin there are 15 to 20 prairie reserves. The original prairie in this state “covered large areas of southern and southwestern Wisconsin, including major parts of Racine and Kenosha counties and extending into three- or four-square miles of Franklin.”

“A prairie,” said Whitford “is not just a sea of grass. Wildflowers may dominate at certain seasons.” In remnants of prairies found along railroad rights-of-way and in abandoned cemeteries 60 to 80 species of prairie plants may be found in an area only several yards wide by 100 yards long”

True prairie soil which takes “centuries to develop” is also a complex mixture, including minerals, millipedes, pill bugs and bacteria, insects, fungi, algae and earthworms, said Whitford. The Whitnall prairie, which was established on forest subsoil, has not yet developed such a true prairie soil. As a rough estimate, ecologists believe that only one inch of prairie soil accumulates in a century.

The animals of the prairie, said Whitford, have an important role to play in aerating the soil. In research on ants in a Platteville prairie, scientists concluded, on the basis of the number and size of the ant colonies, that every inch of soil depth of five feet is aerated every 1000 years. Other animals such as gophers, groundhogs, mice, and other burrowing animals aerate the soil by digging and burrowing and fertilizing the soil with their droppings.

In prairies, there is as much living plant tissue underground as above the surface. Soil is built up to a depth of two to three feet. It is due to this deep, rich soil that native grasslands have been extensively used in food production both here and on other continents, said Whitford. Overtaxing such soils, however, can lead to their destruction, as occurred in the dustbowl days of the 1930s and again, to a lesser extent, in the 1950s. Today’s intensive agriculture may be endangered, said Whitford, since there is an input of five calories in energy supplies (including fertilizer, equipment, fuel to run the equipment, etc.) for every one calorie of food produced in this country. The price of food is bound to increase in the future, he said, as it has already begun doing.

Whitford, whose specialty is plant ecology, also explained some of the intriguing adaptations of the prairie plants. Nearly eight feet high stood the prairie dock and compass plant whose large leaves lie on a north-south line to avoid facing broadly the scorching southern sun. Due to this reliable characteristic, the latter was used as a compass by early settlers who could easily become lost in the tall sea of grass over which they could not see any landmarks.

The leaves of these plants, as well as those of the rattlesnake master with its large white balls of blossoms, are thick and leathery to prevent desiccation during droughts. Even the grasses have leaves well-adapted for prairie life- narrow, tapered leaves to reduce the exposed surface area.

A variety of clovers and other legumes fertilize the prairie with nitrogen-fixing ability. Nodules of bacteria on their roots take in nitrogen from the atmosphere and convert it into nitrogen-containing compounds.

The patterns, textures, and colors of the prairie plants were as interesting as their adaptations. Blazing stars thrust their purple plumes skyward amid the straw-colored hues of coneflowers, goldenrod, and rosinweed. Here and there were purple-petaled coneflower with their orange-tinted centers-their unique color combination strikingly beautiful. Only a weed species, but nonetheless lovely is the Queen Anne’s Lace, a “settler” from Europe, having come in with seed mixtures for hay and pasture crops. The delicate blue chicory flowers were scattered among these lacy white foreigners.

Such was the beauty and interest of the Whitnall prairie that many participants asked questions about establishing prairie plants on their own properties. A heritage, nearly lost has at last been valued and hopefully, will flourish more widely in our yards, our parks, and even perhaps along our expressways and highways. Legislation to come up next month in our state legislature will seek to revise statutes on weeds and may “legalize” some of our native prairie plants.